When one thinks of tomes outlining the natural history of England, the Domesday Book is one that doesn’t usually come to mind. However, this great book does include some tantalizing pieces of evidence surrounding the natural history of England in the 11th century.

Every student of history knows how William the Conqueror commissioned a great survey of the lands of his newly conquered domain in 1085. Yet few people know how the survey began at William’s Christmas court in 1085 or why it was important.

The great Domesday survey was designed to bring “stability” to the collection of taxes to his new domain. William’s council of ministers was constantly burdened with the disruption of taxes through many landholding disputes. This was worsened by the fact that many of William’s new subjects did not recognize the Norman principles of feudal obligations. As a result in 1086, William sent to every shire in England Royal Commissioners with a long list of questions such as; who owned the manor, who had owned it before? Who owned the meadow, the forest, or the eel pond? While William did not live long enough to see the completion of the Great Survey, what was returned by his commissioners was a fascinating document that outlines the structure of England’s physical landscape just after the first millennium.

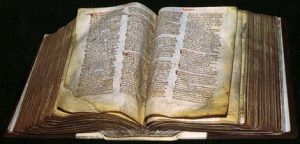

The Domesday Book was actually two distinct surveys; The Little Domesday Book surveyed the eastern part of England (Essex, Norfolk, and Suffolk) while Great Domesday surveyed the rest of the nation. The surveys were notoriously inconsistent in the recording of landholdings. To make matters worse, Domesday was written in eleventh century clerical Latin that was highly stylized and abbreviated making translation nearly impossible without specialized training. English translations did not even appear in published form until the 19th century. However, even with these issues, Domesday offers the natural historian a wonderful, although somewhat skewed “snapshot” of the scope and scale of the physical environment of England at the time. Here are a few of the gleanings about the physical environment that Domesday provides:

- England’s human population. Although Domesday was not a formal census, the Commissioners were tasked to record the heads of households of villagers, cottagers, slaves, freemen, sokemen, and of course the manorial Lords. An estimate of the total population can be obtained with a type of multiplier. It is also important to note that the City of London, Winchester, and some other English towns were also not included in the survey. This was probably due to their tax-exempt status. Church officials, monks, and nuns were also not included. Even with an estimate, it can be seen from Domesday that the most densely populated areas of rural England at the time we’re in the eastern areas of Lincolnshire, East Anglia, and East Kent (approximately 10 people per square mile). As the surveyors proceeded northward, the population became much more sparse (approximately 3 people per square mile). These estimates show a dramatic decline in population from Roman times when it was thought to have exceeded approximately 4 million people.

- Woods, forests, game-parks, and agricultural land use. Domesday spends a great deal of effort recording the size and scale of agricultural land. It also painstakingly records the size of local woodlands, grazing meadows, pastures, and fisheries. The reasons for this are obvious, William wanted an estimate of potential taxation revenue from agricultural lands but also an idea of the size of potential hunting and grazing rights that could be granted to nobles. Like human population size estimates, land usage is also a “guess” due to the lack of standards in recording area sizes. For example, in some manors land is sometimes described as a unit of measure called a “hide”. The size of “hides” could vary widely between regions of England since it has been speculated that it was an area of land a man needed to feed his family for a year. As a result, a “hide” was smaller in more fertile areas. Woodland, meadow, and pasture land were also sometimes estimated by the size of how many pigs could “free graze” upon it. This of course could also vary widely between fertile and less fertile areas of the country.

Even with the lack of scientific precision in the survey, a good deal of knowledge of the rural landscape at the turn of the millennium England can be constructed. While much scholarly research has been done on Domesday from an economic/political-historical perspective, there has not been much research done on the physical landscape and natural environmental aspects. There are a couple of interesting questions scientists could consider:

- Are woodlands, pastures, and meadows approximately the same size as today?

- How large approximately were the fens, marshlands, and other “unairable land” as compared to today?

- Are there any hints to the number of “wild beasts” that inhabit the hunting areas of England and how does it compare to today’s environment?

Amazingly over 90 percent of the towns and villages listed in Domesday are still there in England today! Here is hoping that more research will be done on this amazing document from the perspective of England’s natural history.

For anyone interested in pursuing this topic further, I would recommend not attempting to read clerical Latin in the original document, but rather invest in or borrow from the library a good “summary” book. Most of the details of this post were taken from an excellent summary book of Domesday called “The Domesday Book: England’s Heritage, Then and Now” by Thomas Hinde (Editor). This stunningly beautiful book provides an overview of each of the towns and manors surveyed. It also goes into a detailed account of the history of the survey and provides an explanation of how Domesday entries were recorded. It also includes some beautiful pictures, maps, and local illustrations for your enjoyment.

Thank you for reading our Blog Post! This review was written with the assistance of “Grammarly”. Grammarly is an amazing FREE tool that allows anyone to write like a professional! For more information and a free download, click here.

For our Reviews of excellent books on Natural History, Archaeology and Technology, please visit our main website!